Raul Fattore

January 14, 2026

Table of Contents

Summary

A new atomic model is introduced, based on the electron morphology theory derived from extensive experimental research initiated by Compton and further refined by Bostick. This model, which is validated by experimental results, presents a finite-sized atom with defined dimensions and energy, in contrast with the traditional “point particle” concept of infinite energy. The proposed atomic model accounts for all currently known subatomic particles and predicts the existence of potential new ones based on the well-established electrodynamic laws. This atomic model was developed without invoking randomness and non-causality, as quantum theory does, which cannot adequately explain the physical world. The model provides robust explanations for various physical properties of elements and particles and for discrete energy levels from the finite size of a real atom rather than the “magical” energy jumps of quantum models. It further demonstrates the origins of discrete energies, as well as Planck’s and Rydberg’s constants. Experimental validation confirms that the total energy equation accurately predicts known atomic spectral lines and forecasts new ones yet to be observed. The derivation of a real-valued atomic wave function challenges Schrödinger’s imaginary wave function, asserting that a real physical world finite-sized particle must possess a real-valued wave function rather than an imaginary one. The proposed modern atomic model offers a superior framework for understanding the physical properties of particles and elements, surpassing other models by providing true physical insight supported by experimental data and the universal electrodynamic laws.

Acronyms, Abbreviations, Keywords

EMW: electromagnetic wave

EMR: electromagnetic radiation

EMF: electromagnetic field

enel: energy element

basel: basic element

Abstract

A new atomic model in modern physics is a real need, especially due to the endless discovery of new “subatomic particles,” which at the time of writing are over 200 and counting [1]. Both the concept of an atom and the widely accepted atomic theory of a nucleus surrounded by orbiting electrons are totally invalidated by this evidence.

Almost 2400 years ago, Democritus defined the atom as the smallest physically indivisible and indestructible piece of matter.

From the end of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th century, diverse atomic models have been developed by physicists in an effort to explain their experimental results. The most widely accepted atomic model states that an atom is composed of electrons orbiting a nucleus made up of protons and neutrons.

The “physically indivisible” atom notion is violated by this atom model, that is provided in textbooks and even mentioned in papers by well-known scientists. It is incorrect to refer to the model of an atom made up of protons, neutrons, and electrons as an atom. In other words, a specific collection of charges makes an element with certain properties. It is divisible and modifiable. It may also be referred to as “basel”.

The planetary model of the atom is invalid, since it violates Ampere’s and Faraday’s laws for orbiting electrons, as they are required to radiate, lose energy, and fall towards the nucleus, which will collapse the atom.

In spite of this violation, a theory on the basic structure of the hydrogen atom was developed using the planetary model. Based on that, certain calculations had been carried out, and obscure non-physical explanations for some sort of “magical energy jumps” were provided in order to give the electron different energy levels based on its “orbital” radius.

The mistaken notion of particle-wave duality originated from the electron’s periodic motion, which led to the assignment of a wavelength to it.

Later, the unfortunate attribution of dual particle-wave behavior to the electron gave rise to a non-physical wave function, such as the imaginary wave function described by Schrödinger. While real-valued observations define the real world, this theory is based on a complex-valued wave function that describes an unreal, non-physical world.

- Is there a physically realistic new atomic model?

- Can this new atomic theory explain all discovered “subatomic particles”?

- Can this atomic theory predict the discovery of new “subatomic particles”?

- Is this theory able to give real-world physical explanations of atomic energy levels?

- Is the new atomic theory compatible with experimental results?

- Do the laws of electrodynamics and energy conservation hold to this new atomic model?

The development of this study will provide answers to all of these questions based on the universal laws of electrodynamics.

Introduction

After conducting numerous experiments, Arthur Compton found that the electron is not a sphere but rather a “ring of electricity” [2]. This discovery contributed to defining the fundamental idea of developing a new atomic model.

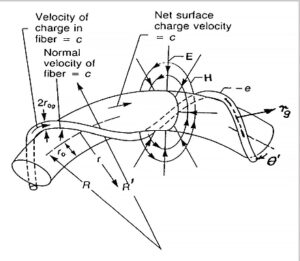

Bostick’s toroidal charge fiber ring

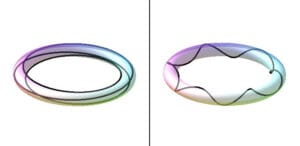

One of his students and an excellent experimentalist, Bostick, published his first torus model for particles in 1956. He continued to refine it until he came up with the idea of a toroidal charge fiber helix for the electron [3] (Figure 1).

Since then, the toroidal ring model of particles has been further improved by David L. Bergman and J. Paul Wesley in 1990 [4, 5].

The elementary particle spinning toroidal charge fiber helix model outperforms all earlier quantum models.

The three main characteristics of the model are the real physical size of the particle, the magnetic dipole behavior of the particle, and the lack of continuous radiation of a spinning ring with static electric and magnetic fields.

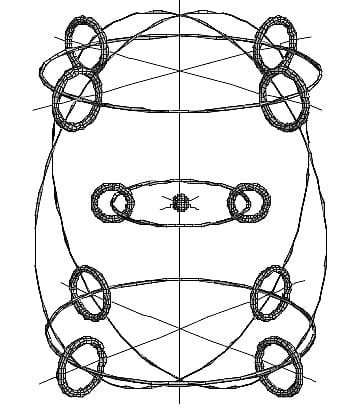

Example of atomic particle arrangement

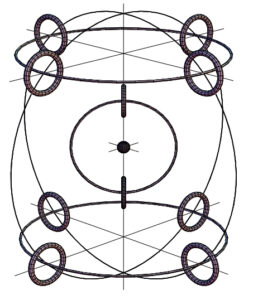

A more physically realistic atomic model was developed by Joseph Lucas and Charles W. Lucas, Jr. in 2002 as an outcome of the spinning ring of elementary particles [6].

This atomic model, which describes how the constituent particles may be packed in the atom according to the balance of electromagnetic forces, is validated not only by theory but also by simple real-world experiments (Fig. 2).

The finite size of particles, their internal structure, and their ability for elastic deformation serve as the foundation for the suggested Lucas model. Compared to earlier atomic models, this one is more fundamental.

Electrons do not orbit the nucleus in this atomic model. Due to the balance of electromagnetic forces, they are positioned at a stable equilibrium distance from it.

Lucas’ atomic model demonstrates the spatial organization of electrons in shells, explains the origin of the seven periods in the periodic table, and explains the fundamental causes for atomic and nuclear magic numbers. Moreover, it also predicts the shell’s organization of nucleons. We know that the nucleus contains two types of particles: protons and neutrons.

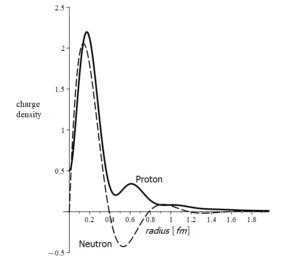

Charge density of proton and neutron

Within the nucleus, neutrons are stable. However, outside the nucleus, the neutron has a half-life of less than 15 minutes and decays into a proton and an electron (plus a “particle” known as an antineutrino, which indeed is a small release of energy from the unbinding process).

The neutron’s mass is practically identical to the sum of the masses of the proton and electron. According to its radius, the neutron’s charge density varies between positive and negative values (Fig. 3).

Based on these results, the neutron may be a bound combination of an electron and a proton rather than a legitimate elementary particle [7].

As a result, Lucas’ atomic model precisely describes how the balance of electromagnetic forces causes electrons and protons to be extremely closely packed in shells in the nucleus.

The New Atomic Model

The most advanced and physically realistic structure that serves as a “basel” in contemporary physics is the atomic theory and model proposed by Lucas. It is based on the established laws of electrodynamics, takes into account the elasticity of the particles, and does not violate any physical laws, making it significantly superior to all existing models in explaining a wide range of physical events.

However, because the Lucas model is divisible and able to change it cannot be considered to be an atom according to Democritus’ definition. It only depicts a particular set of charges that constitute an element with specific properties, or “basel.”

Later on, Lucas realized that Bostick’s model for the electron, which featured the closed-loop charge helix, could be altered to create the model for the real atom that is consistent with Democritus’ definition [8].

The new atomic model, which is based on experimental results [2, 3], gave rise to the Classical Electromagnetic Theory of Elementary “Particles” [9] based on the Charge-Fiber Ring Model of Elementary “Particles” (Fig. 1). This theory seems superior to the Standard Model of Elementary “Particles” [1].

The elementary closed-loop charge helix is the new atomic model

The charge “fiber” or “string” is an end-to-end closed loop helix that forms an imaginary ring or torus (Fig. 3a).

This elementary charge helix can have a charge of +e/3 or -e/3, where e is the electron charge, and has a combined rotational and translational motion along its central axis with either left-handed or right-handed helicity.

Electromagnetic energy can be absorbed by the elementary closed-loop charge helix (Fig. 3a) and kept “trapped” as a standing wave. Multiple resonant states are supported by it. Quantization is the outcome of this wave confinement, meaning that discrete states with discrete energies exist. This energy has the possibility to radiate eventually.

Bostick’s experiments with plasma from 1956 to 1985 suggest two types of “rope-like” organizations of the elementary charge helices [9]:

- An elementary charge helix can be intertwined with two or more charge helices.

- Elementary charge helices can be packed inside other helices. A big primary helix may consist of smaller intertwining secondary helices bound with higher binding energy, which in turn may consist of very small intertwining tertiary helices bound with very high binding energy.

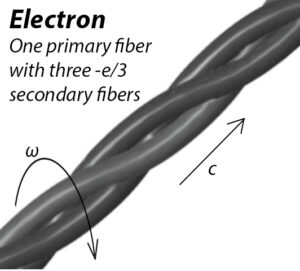

Three elementary charge helices make up the electron.

A brief segment of the electron toroidal ring is visible in Fig. 4. The electron is composed of a single primary fiber with three elementary intertwined charge helices that are closely spaced, tightly bound, and balanced by electromagnetic forces. They don’t normally come into contact with one another. Strong external forces have the potential to totally unbind the elementary charge helices, breaking this structure.

The levels of subdivision of the elementary charge helix are unknown, but taking three levels (primary, secondary, and tertiary) is sufficient to explain all the known “particles” up to date.

According to Bostick’s experiments [3], an electromagnetic vortex is the underlying cause that creates the elementary charge helix. This vortex has soliton properties and is analogous to those found in fluids.

This remarkable discovery highlights two key properties of the elementary closed-loop charge helix:

- The elementary charge helix originates from electromagnetic fields.

- The elementary charge helix can be reflected, refracted, diffracted, and transmitted over extraordinarily long distances through practically any medium without losing energy or degrading in any manner whatsoever.

Bostick developed the elementary charge helix model by employing classical electrodynamics. The “particle-wave duality” behavior is made clear by the second property, which does not require quantum theory.

Since the helix’s properties suggest that it cannot be divided nor destroyed, we may conclude that the elementary toroidal charge fiber helix is the real atom.

Mathematical Model of the New Atomic Theory

Neither the electron theory formulated by Bostick nor the particle theory developed by Lucas provided a definitive mathematical model that supported the theory being proposed.

Any physical theory that takes into consideration “point particles” is invalid. A point doesn’t exist and has no dimensions. As a result, it cannot be given any physical attributes. Dimensions must be taken into consideration in real-world physics.

Even though the new atomic model proposed in this study has tiny dimensions, they are not zero, which means that the energy can be huge but not infinite, as is the case when considering unphysical “point particles.”

The regular toroidal helix parametric equations provide a mathematical model that describes the atom as a toroidal charge fiber helix “line.”

x=\left(R+r_h\cos{\left(\omega_ht\right)}\right)\cdot\cos{\left(\omega_Rt\right)}

y=\left(R+r_h\cos{\left(\omega_ht\right)}\right)\cdot\sin{\left(\omega_Rt\right)}

z=r_h\sin{\left(\omega_ht\right)}

\vec{r}\left(t\right)=x\hat{i}+y\hat{j}+z\hat{k}

Where:

R: torus radius

r_h: helix radius

\omega_h: helix rotational frequency

\omega_R=\frac{c}{R}: helix translational frequency (or torus frequency), where c is the speed of light

\vec{r}(t): position vector

But since a “line” has no dimensions, we must build the fiber with a specific thickness.

In order to define the surface of the fiber around the helix’s central axis, we need to create a local orthonormal basis (Frenet-Serret frame) on the helix consisting of tangent, normal, and binormal vectors (\vec{t}, \vec{n}, \vec{b}). Next, the toroidal charge fiber helix can be calculated by:

\vec{S}=\vec{r}(t)+r_f\cos{\left(\omega_ft\right)}\hat{n}\left(t\right)+r_f\sin{\left(\omega_ft\right)}\hat{b}\left(t\right) (1)

Where:

\vec{r}(t): position vector of the regular helix “line”

r_f: helix fiber radius

\omega_f: fiber “constructor” frequency

\hat{n}\left(t\right): unit normal vector

\hat{b}\left(t\right): unit binormal vector

In order to make some approximations, let’s consider a few typical values of particle dimensions before formulating our final equation.

Dimensions of “Free” Particles at “Rest” and in Different Scenarios

Since neither of the two assumptions in quotation marks exists in the cosmos, they are in fact non-physical. A particle must be isolated and not be subject to any force in order to be considered “free,” which is untrue. There is no “rest” state in the cosmos. Considering that the universe is not known to reach zero degrees Kelvin, radiation causes all particles to vibrate in some way.

Because these particles are elastic, they may change their size and expand and contract to fit into the environment. No particle can be given a constant size value. In a “basel,” an electron in proximity to the nucleus will have a smaller radius (higher energy) than an electron standing farther from the nucleus, having a larger radius (lower energy).

Several features and physical properties can be determined by the toroidal charge fiber helix model for the electron and proton [7]. Among them are the physical dimensions derived from the toroidal parameters, the origin of De Broglie and Compton wavelengths [3], the origin of the particle spin given by \frac{\hbar}{2} [4], the origin of the Rydberg constant [6, Part 3] and the origin of the Planck constant [4] as described below.

h=\frac{q^2}{2\pi\varepsilon_0c}\cdot\ln{\left(\frac{8R}{r_h}\right)} (1a)

The torus-to-helix radius ratio must be constant, as defined by equation (1a).

The fine structure constant \alpha defined for the magnitude of the “elementary charge” e (electron/proton) is \alpha=\frac{q^2}{2\varepsilon_0ch} (1b). Replacing (1b) in (1a) and solving for the radii ratio, we get:

\frac{R}{r_h}=\frac{\mathrm{e}^\frac{\pi}{\alpha}}{8}\approx{10}^{186}Here are some examples of particle sizes [7].

R=3.86\ {10}^{-13}\ [m]: radius of a “free” electron

R=5.7\ {10}^{-16}\ [m]: radius of a nuclear electron (recall that the neutron is a proton-electron bound)

R=1.85\ {10}^{-12}\ [m]: electron radius for aluminum radiation scattering [2]

R=2.1\ {10}^{-16}\ [m]: radius of a “free” proton

R=1.7\ {10}^{-16}\ [m]: radius of a nuclear proton

r_h\cong4\ {10}^{-199}\ [m]: helix radius for the “free” electron

r_f\cong4\ {10}^{-200}\ [m]: estimated fiber radius for the “free” electron

We can assume that the atom in each case may have some similar dimensions as those above since particles are made up of a specific number of elementary toroidal charge fiber helices, which is the real atom.

Dimensions of the New Atomic Model and Atomic Fine Structure Constant

The standard fine structure constant is defined for the elementary charge of the electron or proton.

The contemporary atomic model consists of a charged helical fiber with a charge magnitude one-third that of the electron or proton, having a positive or negative sign based on its helicity, denoted as \mp\frac{e}{3}, resulting in an atomic fine structure value of:

\alpha_a=\frac{\left(\frac{e}{3}\right)^2}{2\varepsilon_0ch}=0.0008080816715\approx\frac{1}{1237} (1c)

All of the more than 200 “subatomic particles” discovered so far consist of numerous elementary charge fiber helices, or the real atom [9]. Depending on the characteristics of electromagnetic interactions among various particles, we may expect composed energy peaks in the energy spectrum.

We might find that some “single” energy peaks are actually split into two or more energy peaks if the measurement instruments’ frequency resolution is high enough. The term “hyperfine structure” was used when double energy peaks were first discovered. Nevertheless, unlike the fine structure constant, this concept was not ascribed to a single constant.

The atomic fine structure constant given in (1c) could be the answer to having a more fundamental constant capable of explaining the hyperfine structure.

The radius R of the particle we were previously considering, which consists of several fibers, is nearly identical to that of the atom, which is made up of a single fiber. The correlation between the torus ring radius and the charge fiber helix radius is now the following, after taking into account the atomic fine structure constant given in (1c):

\frac{R}{r_h}=\frac{\mathrm{e}^\frac{\pi}{\alpha_a}}{8}=3.24\times{10}^{1687} (1d)

Assuming the torus radius for the free electron and the nuclear proton as given in previous paragraphs, the charge helix fiber radius is r_h\approx{10}^{-1700}\left[m\right] and r_h\approx{5\ 10}^{-1704}\left[m\right], respectively.

Equations of the New Atomic Model – The Toroidal Charge Fiber Helix

New atomic model as a toroidal charge fiber helix

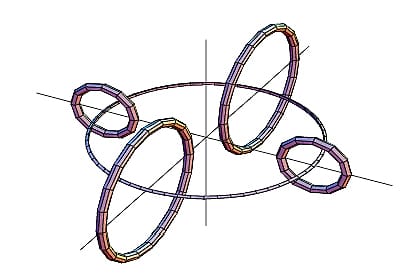

The final parametric equations of the toroidal helix are approximated due to the extremely small values of r_h and r_f. This yields the example helix (not in scale) illustrated in Fig. 5 and provided by the following equations:

x=\left(R+r_h\cos{\left(\omega_ht\right)}-r_f\cos{\left(\omega_ft\right)}\right)\cos{\left(\omega_Rt\right)}

y=\left(R+r_h\cos{\left(\omega_ht\right)}-r_f\cos{\left(\omega_ft\right)}\right)\sin{\left(\omega_Rt\right)} (2)

z=r_h\sin{\left(\omega_ht\right)}+r_f\sin{\left(\omega_ft\right)}

\vec{r}=x\hat{i}+y\hat{j}+z\hat{k}

Keep in mind that for a smoother approximation of the fiber surface, the fiber “constructor” frequency \omega_f should be as high as feasible. The condition is \omega_f\gg\omega_h. The fiber surface approximation is better the higher \omega_f.

Parametric equations (2) make the base of the mathematical model of the new atom.

The Origin of Discrete Atomic Energies or Frequencies

As we have already mentioned, the actual atom is the toroidal charge fiber helix, an elastic particle with an infinite self-field, that expands or contracts in response to its surroundings. A shift in size indicates a shift in energy or frequency.

The helicoidal fiber has a certain charge distributed homogeneously on its surface. Energy conservation requires that the helix be continuous; that is, the start cross-section must be the same as the end cross-section, a condition that is given by a closed-loop helix along the torus circumference.

From the parametric equations we have seen that the new atomic model is subject to a combined rotational and translational motion given by \omega_h and \omega_R, respectively. The continuous charge along the helix, when set in motion, will create a standing EMW, which is confined or “trapped” along the circumference of the torus. The structure behaves similarly to a toroidal cavity resonator.

Now, let’s calculate the length of one cycle, or wavelength, of the toroidal charge fiber helix derived from Eqs. (2), which is given by:

\lambda_{h}=\int_{0}^{\frac{2\pi}{\omega_{h}}}{\|\mathit{{\dot{{\vec{r}}}}}\|}d t \approx 2\pi R \frac{\omega_{R}}{\omega_{h}} (3)

If we call the frequency ratio n=\frac{\omega_h}{\omega_R}, we get:

n\ \lambda_h=2\pi RWhere 2\pi R\ =\ \lambda_C is the Compton wavelength [3].

Thus, the origin of energy or frequency “quantization” has been derived from the basic toroidal charge fiber helix equations.

New atomic model with n=1/3 sub-harmonics (left) and n=6 harmonics (right)

There are standing waves with one or more wavelengths around the circumference of the torus:

n\lambda_h=2\pi\ R (4)

Additionally, standing waves with a wavelength equal to multiple times the ring’s circumference, \lambda_h=\frac{2\pi R}{n}, are feasible. Where n=1,\ 2,\ 3,\ … represents the harmonics and n=…\frac{1}{4},\ \frac{1}{3},\ \frac{1}{2},\ … represents the sub-harmonics, as seen in the example given on Fig. 6.

A closed-loop helix around the torus must exist for stability and energy conservation. The frequency ratio must always be a rational quantity of two integers > 0 in order for this condition to happen. This means that the discrete number n can also be a ratio of integers and not always an integer.

The new atomic model can be defined as the fundamental “enel” that constitutes the most elementary spatial energy storage.

The Total Energy Equation Determines the Atomic Energy Levels

There is no reason for the laws of electrodynamics not to be valid at atomic scales. There is no such thing as “nuclear strong force” or “nuclear weak force.” There is only one force in Mother Nature that is valid on any scale: the Universal Electrodynamic Force. It can clearly explain atomic and nuclear interactions without any need to create any new forces, as in quantum theory.

For the first time in physics, a true total energy equation has been formulated, including terms accounting for potential energy and kinetic energy depending not only on velocity but also acceleration.

The Total Energy [11] of moving charges is derived from the Universal Electrodynamic Force, which gives us an accurate energy equation. You can find more details in the article Nuclear Fusion Enhanced by Negative Mass – A Proposed Method and Device – (Part 2).

The Total Energy equation has three terms:

1) The Potential Energy term, which depends on the relative position of the charges.

2) One Kinetic Energy term, which depends on the relative velocity of the charges.

3) One Kinetic Energy term, which depends on the relative acceleration of the charges. This term accounts for radiation energy and is not found in scientific literature as being part of the total energy of the system.

E=\frac{1}{\sqrt{1+\left(\cos^2{\left(\theta\right)}-1\right)\frac{v^2}{c^2}}}\cdot\left(kq_1q_2\cdot\left(\frac{1}{r_f}-\frac{1}{r_i}\right)-\frac{kq_1q_2}{c^2}\cdot\left(\frac{1}{r_f}-\frac{1}{r_i}\right)\cdot v^2-\frac{2kq_1q_2\cos{\left(\alpha\right)}}{c^2}\cdot\left(\ln{\left(r_i\right)}-\ln{\left(r_f\right)}\right)\cdot a\right) (5)

The total energy is defined by Eq. (5), where E is the total energy of the system, r_i and r_f are the initial and final distances between the charge centers, c is the speed of light, r,\ v,a are the relative distance, velocity, and acceleration between the charges, \theta is the angle between \vec{r} and \vec{v}, and \alpha is the angle between \vec{r} and \vec{a}.

The initial distance is usually taken such that the rest energy of the system is approximately zero, which usually means r=\infty. But as infinity is not a defined number, let’s take a practical value from Mother Nature that can realistically be used instead. Infinity can be replaced by a huge distance, approx. x10 bigger than the oldest light we have observed from the “Big Bang” ({46500\ 10}^6ly={4.410}^{26}m). To go safe, we’ll take r_i={10}^{27}m.

However, zero energy does not just happen when charges are at rest and separated by large distances. As demonstrated in the article “Nuclear Fusion Enhanced by Negative Mass – A Proposed Method and Device (Part 2),” there is a second solution to Eq. (5) that, depending on the system dynamics, yields zero energy for a specific close distance. For the first time in physics, it has been found that zero energy is impacted not just by potential energy but also by the system’s dynamics.

As we can see in Eq. (5), the total energy is affected by a factor \gamma_E=\frac{1}{\sqrt{1+\left(\cos^2{\left(\theta\right)}-1\right)\frac{v^2}{c^2}}} that is physically realistic compared to the known “Lorentz factor”, because it also takes into account the type of motion that is given by the angle \theta between \vec{r} and \vec{v} (the relative position and velocity). Note that the “Lorentz factor” is only valid for circular motion. Also note that 1\le\gamma_E\le\infty depending on the angle \theta between \vec{r} and \vec{v} and the relative velocity, reaching a maximum value (or \infty) for \theta=\frac{\pi}{2}.

We can write the total energy of the system in short form as:

E=\gamma_E\left(U+K+E_{rad}\right) (6)

The “rest energy” is no other than the potential energy “U” when the kinetic variables are zero (v=0 and a=0). The Universal Force shows us that zero velocity doesn’t mean that acceleration should be zero. Note that in this case \gamma_E=1. Under such conditions, the rest energy is:

E=E_0=UThe “rest energy” depends on the distance between the centers of charges.

We successfully applied the Total Energy equation, among other things, to precisely calculate the real released energy in nuclear fusion [12] and the single energy of the products, including radiation energy. For more details, read the section “How to Calculate the Real Released Energy and the Single Energy of the Products” in the article Nuclear Fusion Enhanced by Negative Mass – A Proposed Method and Device – (Part 3).

Equation (5) can be used to calculate EMR absorption or emission indistinctly. It is merely a sign change due to the angle \alpha (head-on motion or the opposite).

Radiation Energy is Proportional to Acceleration

It is once again demonstrated that the established laws of electrodynamics, which led to the Universal Electrodynamic Force and subsequently to the Total Energy Equation, may effectively be utilized to compute the radiation absorption and emission of nuclei, atoms, and individual charges.

The radiation is caused by the last term in Eq. (5). It states that energy is directly proportional to acceleration and is a logarithmic function of the distance between charges.

This is the law governing the discrete distribution of energy.

A simple equation that gives the relationship between EMW energy and frequency is the known Planck equation:

E=h\ f\ [Joules] (7)

Planck’s equation, however, is unrelated to the wave source that causes that frequency. Equating equations (5) and (7) and solving for f yields a more complete equation that relates wave frequency to the cause. As a result, the wave frequency and wavelength that correspond to an energy level are:

f ={\|\frac{k q_{2} q_{1}}{h} \left(\frac{2a}{c^{2}}\cdot \left(\ln \left(r \right)-\ln \left(r_{i}\right)\right)-\left(1-\frac{v^{2}}{c^{2}}\right)\frac{\left(r -r_{i}\right)}{r r_{i}}\right)\|}\left[\mathit{Hz} \right] (8)

\lambda ={\|\frac{h \,c^{3} r r_{i}}{k q_{1} q_{2} \left(2 a r r_{i}\cdot \left(\ln \left(r \right)-\ln \left(r_{i}\right)\right)+\left(r_{i}-r \right)c^{2} \left(1-\frac{v^{2}}{c^{2}}\right)\right)}\|}\left[m \right] (9)

Eq. (8) clearly shows that the radiation frequency (energy) is proportional to the charges’ relative acceleration.

The logarithmic function of distance causes the spacing between adjacent lines of the spectrum to gradually decrease as the wavelength of the lines decreases until it converges at some distance limit.

Self-Energy of the New Atomic Model

The self-energy of a particle is an ideal, non-physical condition that does not exist in the universe since it requires that the particle be “isolated” and at “rest” (with absolutely no forces acting on it).

A charged particle’s self-energy is its electromagnetic field energy when there are no external forces operating on it. The self-energy of a particle in total isolation is determined by its charge magnitude and electrodynamic characteristics. It does not depend on the particle’s mass.

Because a point lacks dimensions, the “point particle” assumption yields infinite energy. Only for finite-size particles will energy have a specific value, something that has no clear definition in quantum theory.

To handle the infinite energy associated with “point particles,” one method to determine self-energy in quantum theory employs probability-based diagrams and contains an operator with a complex value, with the real part representing self-energy. This “method” sounds more like a fairy tale or science fiction than actual physics. Furthermore, complex numbers do not describe the physical world.

Another “method” to determine self-energy is a widely used calculation of particle self-energy defined as a “mass-energy” calculation. Even when we are dealing with charges, the “mass-energy” calculation completely overlooks this reality and uses the traditional lump Newtonian mass.

In what follows, we’ll first analyze Bostick’s electron model and some properties, which is the base for the new atomic theory. After that, the new atomic model will follow, with calculations of self-energy and other quantities. The wrong results given by the “mass-energy” calculation will be put in evidence.

Self-Energy of the Electron

Bostick [3] devised the gravitationally stabilized toroidal fiber ring model of the electron using electrodynamics. The particle’s real size exhibits a variety of physical characteristics that fully explain energy quantization, the origin of Compton and De Broglie wavelengths, the origins of the Planck constant, and other physical properties.

Lucas has modified and extended this particle model to include all known particles, yet there is no better particle model capable of explaining the experimental findings than this one [9].

Bostick’s calculations of energy for a gravitationally equilibrized electron fiber take into account that gravitational energy must be equal to electromagnetic energy, which gives the following result:

E={27\ 10}^7\left[J\right]\approx{1.7\ 10}^{27}\left[eV\right] (10a)

We see that the energy is huge but not infinite. The frequency corresponding to this energy is:

f=4.07\ {10}^{41}\left[Hz\right] (10b)

For our calculation, we’ll enter the motion variables from the toroidal charge fiber equations (2) into the total energy Eq. (5). We assume that both electrons’ primary fibers are very far away from each other and moving in very slow radial motion, where \theta=\alpha=\pi makes \gamma_E=1. In this scenario, the relative velocity and acceleration between the particles will be nearly zero, leaving only the velocity and acceleration caused by the particles’ own structure, so that the self-energy is given by:

E=kq_1q_2\left(\frac{1}{r}-\frac{1}{{10}^{27}}\right)-\frac{kq_1q_2}{c^2}\cdot\left(\frac{1}{r}-\frac{1}{{10}^{27}}\right)v^2-\frac{2kq_1q_2\cos{\left(\pi\right)}}{c^2}\left(\ln{\left({10}^{27}\right)}-\ln{\left(r\right)}\right)\ a (11)

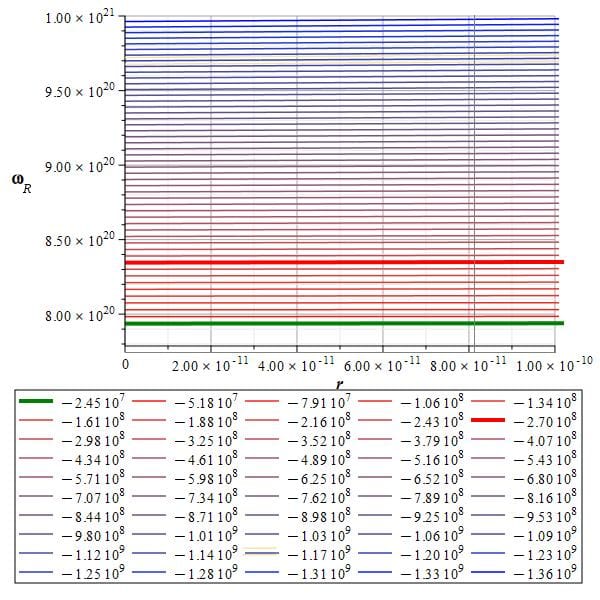

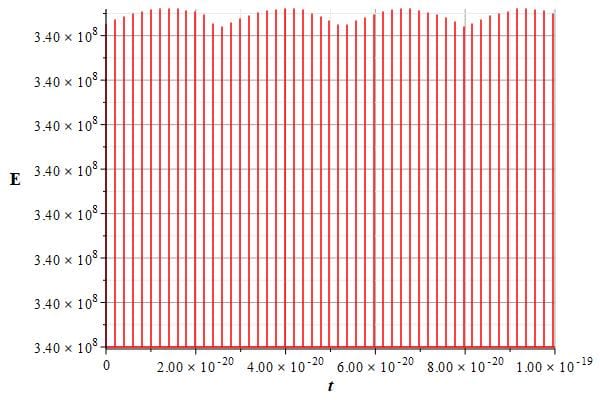

The graphs that follow were made by taking the “free” electron radius of R=3.8\ {10}^{-13}[m] and making the fiber helix frequency equal to the toroidal frequency \omega_f=\omega_R, that is, n=1, so that the electron is not subjected to any harmonics or subharmonics oscillations.

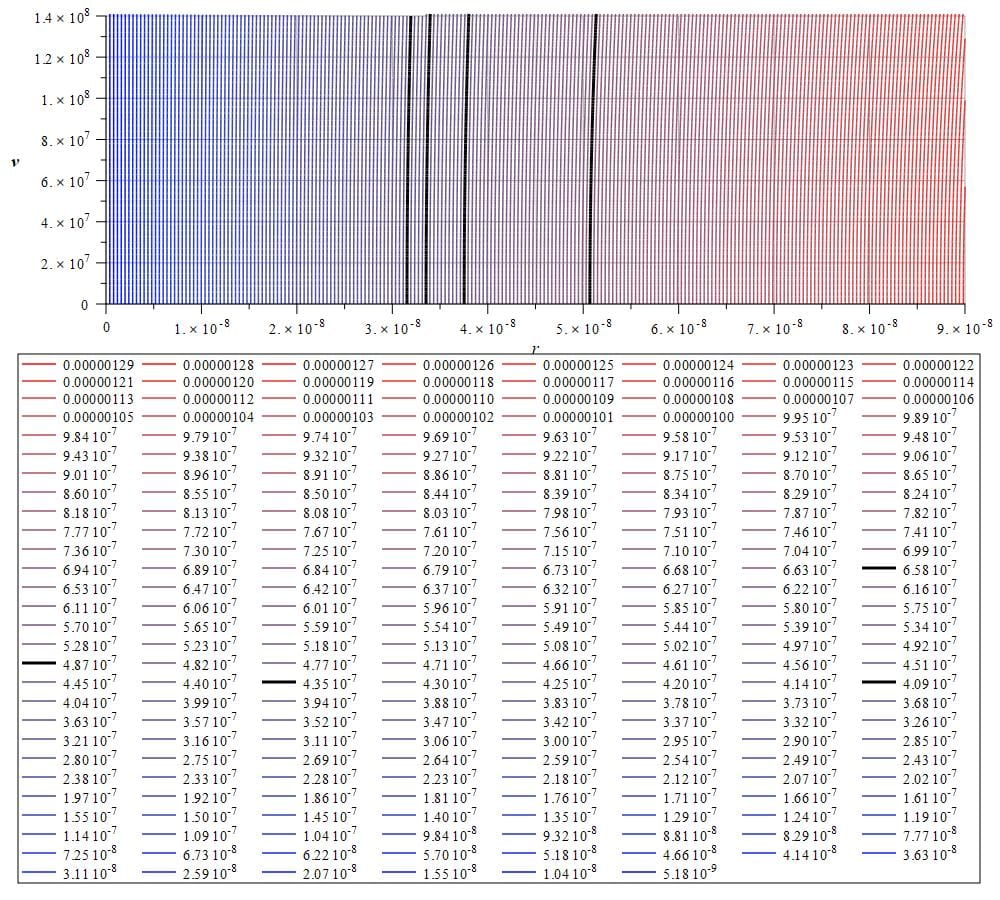

The self-energy of the electron (red line) and self-energy of the new atom (green line) given by the toroidal charge fiber helix

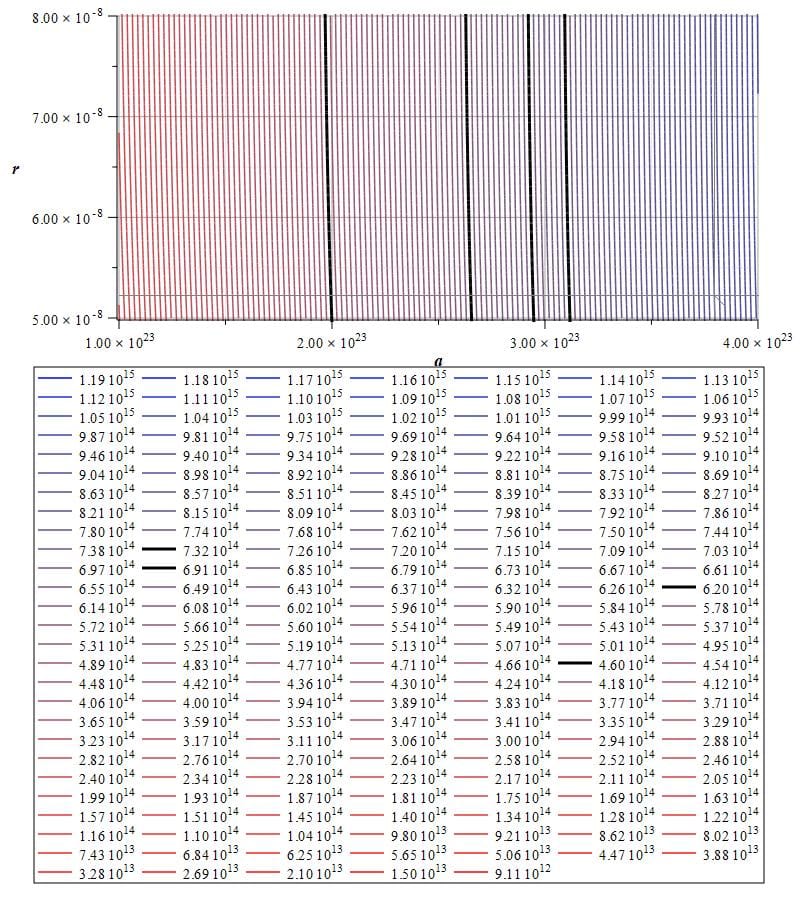

Figure 7 depicts a graph of an electron’s self-energy levels as a function of toroidal frequency \omega_R and relative distance r. Below the graph, we can observe the self-energy values in Joules for the displayed levels.

The green energy line corresponds to the “mass-energy” for the “free electron at rest,” while the red energy line is the energy calculated by Bostick for an electron gravitationally equilibrized fiber.

The toroidal frequency associated with the green line energy is \omega_R=7.9\ {10}^{20}\left[\frac{1}{s}\right].

Applying Planck’s equation, the energy for this torus frequency is: E=8.33\ {10}^{-14}\left[J\right]\approx0.51\ \left[MeV\right]

This energy is precisely the “mass-energy” of the electron.

The toroidal frequency associated with the red line energy is \omega_R=8.3\ {10}^{20}\left[\frac{1}{s}\right].

Applying Planck’s equation, the energy for this torus frequency is: E=8.75\ {10}^{-14}\left[J\right]\approx0.55\ \left[MeV\right]

As a result, Bostick’s calculated self-energy is higher than the “mass-energy” of a free electron, or electron at “rest.”

The self-energy of the electron (red line) from the frequency graph

We may also calculate the self-energy of the electron by using Eq. (8) and making a level graph of the frequency f as a function of the toroidal frequency \omega_R and relative distance r, as it is shown in Fig. 8. The box below the graph displays the frequencies in Hz for the depicted levels.

The thick red line represents approximately the self-energy frequency given by (10b), which corresponds to the toroidal frequency \omega_R=8.3\ {10}^{20}\left[\frac{1}{s}\right].

Applying Planck’s equation, the energy for this torus frequency is: E=8.75\ {10}^{-14}\left[J\right]\approx0.55\ \left[MeV\right]

Which is the same as the result shown in Figure 7.

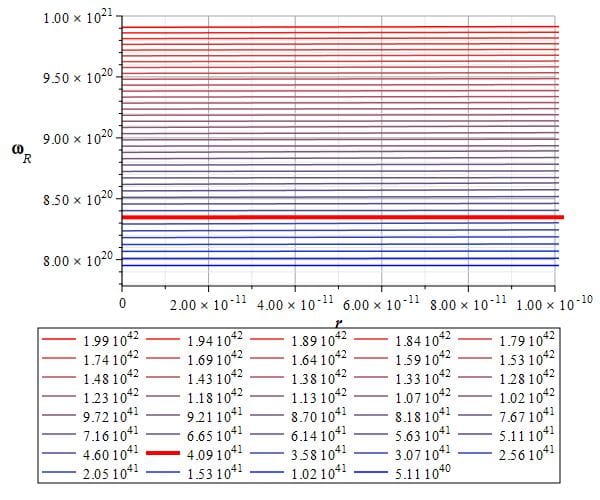

Self-Energy of the New Atomic Model

We already know that our current atomic model consists of a closed-loop, single toroidal charge fiber helix with an elementary charge of \pm\frac{e}{3}, where e represents the electron/proton charge.

The self-energy of the new atom given by the toroidal charge fiber helix

Our modern atom is the most elementary energy storage element, which we call “enel.”

Yet, we can expect similar characteristics to those of the electron and proton, although with different self-energy levels.

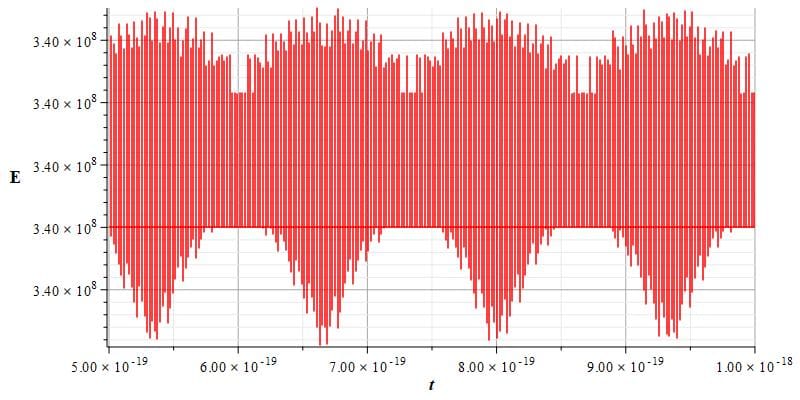

Applying Eq. (11) to the modern atomic model and following the same calculation procedures as in Fig. 7, we obtain the results shown in Fig. 9. The box below the graph shows the self-energy values in Joules for the displayed levels.

The thick green line shows the self-energy value of our contemporary atomic model, which, without considering sign, is:

E=2.73\ {10}^6\left[J\right]\approx1.7\ {10}^{25}\left[eV\right]The toroidal frequency associated with the green line energy is \omega_R=7.9\ {10}^{20}\left[\frac{1}{s}\right].

Applying Planck’s equation, the energy for this torus frequency is: E=8.33\ {10}^{-14}\left[J\right]\approx0.51\ \left[MeV\right]

This energy is exactly the “mass-energy” of the electron, but it is derived from a self-energy value that is \frac{1}{100} that of the electron.

Why do we obtain the same “mass-energy” value as the electron, despite having considerably lower self-energy?

Because the computation is dependent on the toroidal frequency, which was set to the same for the electron and the atom. And that has nothing to do with true self-energy.

This fact demonstrates the possibility of incorrect energy results in the calculations using Planck’s equation E=h\ f\ [J] and Einstein’s “mass-energy” E=m\ c^2\ [J] equation. None of these formulas are related to the electrodynamic interaction of electric charges, none of them provide information about the system’s dynamics, and none of them provide a real self-energy value.

Calculations using those formulas should be done with caution since, as illustrated above, they do not provide the true self-energy value of a charge.

The “mass-energy” calculation, which only takes into account the lump Newtonian mass, does not provide information about particle self-energy. Mass is not a fundamental quantity, whereas charge is [13]. Formulas such as E=m\ c^2 (mass-energy) and E=∆m\ c^2 (mass excess/defect) do not account for charge dynamics, leading to inaccurate results about electromagnetic radiation energy.

Unfortunately, the most dangerous and disastrous application of those formulas is for energy calculations in nuclear fusion, where massive charge accelerations and velocities exist. Radiation energy is typically substantially higher than the results of the mass excess/defect formula and mechanical kinetic energy estimates [12].

A clear demonstration of the dangerous, deficient and obsolete calculation of nuclear released energy given by Einstein’s formula and mechanical kinetics is provided in the section “How to Calculate the Real Released Energy and the Single Energy of the Products” of the article Nuclear Fusion Enhanced by Negative Mass – A Proposed Method and Device – (Part 3), where the real radiation energy in nuclear fusion and the real energy of the products are calculated.

Assuming we make the great mistake of accepting the deficient “mass-energy” calculations, we can say that the modern atomic model’s self-energy value, E=1.7\ {10}^{25}\left[eV\right], serves as the foundation for the most elementary confined “mass-energy,” E=0.51\ \left[MeV\right].

Figures 10 and 11 provide example graphs of energy as a function of time for two different time intervals, revealing very small periodic variations in energy.

Energy of the new atomic model vs. time showing tiny periodic variations

Energy of the new atomic model vs. time showing tiny periodic variations for a different time interval

Atomic Spectrum Predicted by the Total Energy Equation

The total energy equation (5) is a valuable tool for calculating and predicting atomic energy absorption or emission levels. This equation was obtained from the Universal Electrodynamic Force, which was derived from the well-established laws of electrodynamics.

Atomic energy levels showing a logarithmic pattern

The total energy equation is not an empirical approximation. It can be used to determine and predict the atomic spectrum and elements’ spectra without the need for empirical formulas such as Rydberg, Balmer, Lyman, Brackett, Pfund, and others for hydrogen or other elements (“atoms”).

Additionally, using Eqs. (8) and (9), you can easily calculate the frequency and wavelength of the spectral lines.

As demonstrated in Fig. 12, atomic energy absorption or emission follows a logarithmic pattern, resulting in a continuous decrease in line spacing for higher energies until a certain limit.

The “atomic” energy spectrum, or elements’ spectra, is the result of electrodynamic interactions among charges. The number of emitted or absorbed energy lines are not always the same for the same element (“atom”). Particles can reach equilibrium at different energy levels, depending on the environment. That explains the Zeeman and Stark effects.

A valuable feature of the total energy equation is the ability to define a precise “energy range” as well as the number of energy levels that can be identified within that range. In general, we may discover some energy levels that go undetected, either because the electrodynamic conditions were not met or because the detector’s frequency/wavelength resolution is poor.

Applying the Total Energy Equation to Elements

Electron shells and magnetic flux loops in a neon element

To apply the total energy equation to elements (“atoms”), we need to use Ampere’s law. In Fig. 13 we see an example of the electron shell structure for the neon element (wrongly called “atom”), with its central nucleus.

We have already mentioned that electrons do not orbit the nucleus. They are positioned at a stable equilibrium distance from it due to the balance of electromagnetic forces.

The magnetic flux loop, shown by the three thick horizontal circles, maintains electron equilibrium on the large thin circles in the outer shell.

By applying Ampere’s law, we can replace each magnetic flux loop by a circular wire. Then, the three parallel circular loops can be replaced by only one circular loop with the nucleus at the center. The drawback is that the effective radius may not be that of the free electron, but we can get an excellent approximation.

As a result, closed-shell elements (“atoms”) act as if they have a single electron shell enclosing the nucleus, similar to the Bohr model for a hydrogen “atom” with one electron.

The situation for the remaining elements (“atoms”) is less straightforward. If the last outermost electron shell has a number of electrons divisible by four, the symmetry may be reduced to the corresponding ring described above.

For elements (“atoms”) with an odd number of electrons other than one, and in all other cases, the symmetry cannot be reduced to a single loop. A computer modeling program may be necessary to get precise estimations of energy levels, absorption, and emission spectra [6].

The Hydrogen Element (“atom”) is Unstable

Hydrogen element toroidal ring structure according to the new atomic model

If it exists in nature as a free particle pair, the hydrogen element, which consists of one electron and one proton, is an extremely unstable configuration. Such electron-proton bonds are only stable as neutrons in the nucleus if they form a highly compact, sandwich-like packing organization with other nuclear protons [6].

As soon as the neutron is outside the nucleus, it decays into an electron and a proton in less than 15 minutes.

The ideal arrangement of the hydrogen “atom” might be in a coplanar alignment of the toroidal rings, as shown in Fig. 14 (not scaled). Depending on the initial rings’ positions and whether the currents run in the same or opposing directions in each particle (parallel or anti-parallel magnetic moments; ideal “quasi-stable” or unstable equilibrium), there will always be a magnetic non-zero radial net force, which can be attractive or repulsive, besides the Coulomb force.

As particles are elastic, and the electron radius is 656 times larger than the proton, it is hard to imagine that such a configuration can be stable. Consequently, any little disturbance will compromise the structure and displace the particles from their coplanar arrangement, preventing the magnetic moment from restoring the particles to a potential “quasi-equilibrium” state.

The Hydrogen Gas Molecule is Very Stable

Hydrogen molecule toroidal ring structure according to the new atomic model

Thanks to its high stability, hydrogen gas molecules are the most abundant element found in the universe, with an abundance of roughly 75%, followed by helium with approximately 25%.

Figure 15 depicts the arrangement of the hydrogen molecule (not in scale), with the magnetic flux loop strongly binding all four particles and resulting in a very stable, robust configuration.

Hydrogen and helium may have similar charge interactions, with the exception of the neutrons in helium’s nucleus.

At some point, and depending on the electrodynamic environment, hydrogen and helium may have very similar spectral lines.

In what follows, we are going to analyze the spectral emission of the hydrogen gas molecules based on the modern atomic model configuration shown in Fig. 15.

Three Experimental Confirmations of the New Model of Atom

The total energy equation applied to the molecular hydrogen structure shown in Fig. 15 describes not only the electrodynamic interaction of the entire structure but also that of a pair of charges. As a result, we might expect to have an overlay of hydrogen molecule spectral lines as well as lines caused by the electrodynamic interaction of the charge pairs p-p and e-p, the latter of which is incorrectly referred to as “atom.”

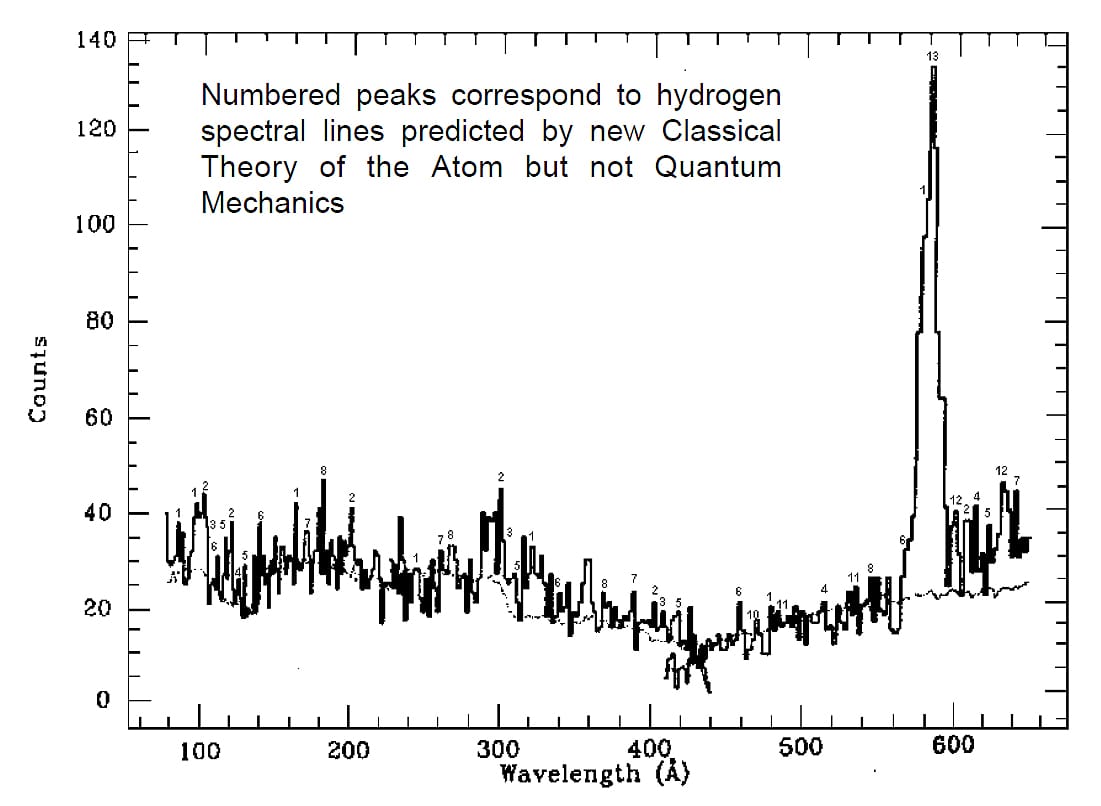

1) In 1991, Labov and Bowyer [14] developed a method for measuring the extreme ultraviolet spectrum from 8 to 65 nm. To get above the earth’s atmosphere, they used a sounding rocket equipped with a grazing incidence spectrometer.

Extreme ultraviolet spectrum for hydrogen and helium

The spectrometer measured the spectrum while flying in the earth’s shadow, heading away from the sun towards a dark area of the universe. This portion of the universe is most likely made up primarily of hydrogen and helium gas. Figure 16 shows the obtained spectrum. There are a lot of spectral lines, or peaks.

By making calculations with a modified Rydberg formula adapted to the new atomic model and for diverse harmonics, Lucas predicted 64 spectral lines for hydrogen in this range of wavelengths, which are the numbers he marked on the spectrum peaks and are detailed at the end of his paper [6, Part 3]. The comment on the graphic was also made by Lucas.

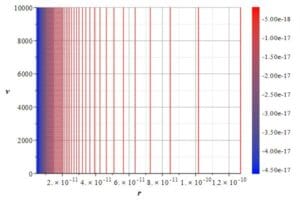

At the time Lucas made his calculations with the modified Rydberg formula, the total energy equation was not available. Our calculation for this spectral range is visualized on the graph shown in Fig. 17. This is a contour or level graph of the wavelength as a function of velocity and distance. The box below the graph contains the wavelengths of the lines in meters. The spectrum range from 8 to 65 nm is approximately delimited by the two thick black lines on the graph.

With our poor and somewhat limited graph, we predicted around 96 lines in that range, including Lucas’ 64 predictions. The total energy equation contributed to improved results and provided experimental support for the contemporary atomic model, eliminating the need to use empirical equations.

2) In 1994, Jean-Yves Roncin and Françoise Launay made an excellent work in atlas format [15] for the ultraviolet emission spectrum of molecular hydrogen. The high-resolution spectrum contains 12,565 lines, extending from 78.60 nm to 171.35 nm.

This extensive work is divided into 165 sections covering approximately 0.6 nm each.

Our graphs, which show findings with only two significant figures, can never provide such a level of detail. It means that we can only plot so many separate lines before they start repeating the same rounded value. If we want to get such a high-resolution spectrum with our total energy equation, we have to solve the equation numerically with the required precision. As a result, we’ll have a very extensive list of lines similar to the atlas of Roncin and Launay above.

The spectrum range from 78.60 nm to 171.35 nm is approximately delimited by the two thick green lines in Fig. 17.

Even with our restricted resolution graph of only 300 spectral lines, the total energy calculation predicts around 150 lines in that range.

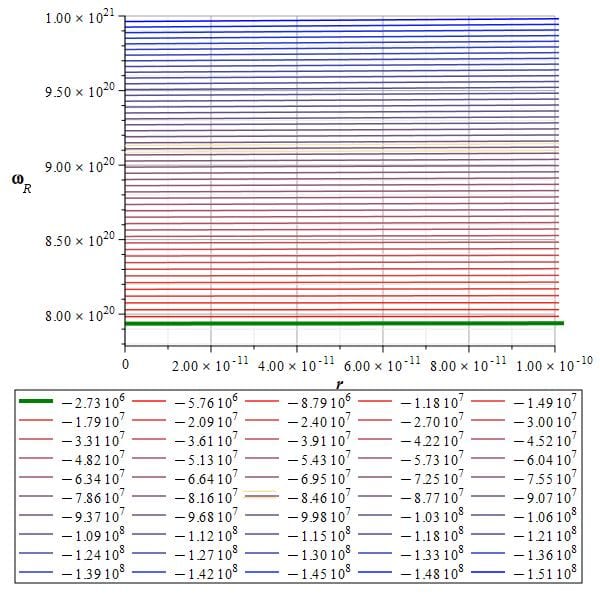

Emission spectrum of molecular hydrogen from 0.617 nm to 185 nm (acceleration was set to a=7\ {10}^{23}\left[\frac{m}{s^2}\right])

3) The four classical emission lines of a hydrogen “lamp” that are widely published are the spectral lines at the following wavelengths: 410 nm, 434 nm, 486 nm, and 656 nm. In Fig. 18 we have a graph of 250 spectral lines ranging from 5.18 nm to 1290 nm. This is a contour or level graph of wavelength with respect to velocity and distance.

The four hydrogen emission lines are represented by thick black lines on the graph, with their wavelengths displayed in meters in the box below the graph. The logarithmic energy law with particle distance is evident. Despite the limited graphic resolution, numerous additional lines are anticipated within the wavelength range. Additional lines or line splitting can be detected due to alterations in the electrodynamic environment, such as the Zeeman and Stark effects.

Emission spectrum of hydrogen from 5.18 nm to 1290 nm showing the four typical lines at approximately 410 nm, 434 nm, 486 nm, and 656 nm (acceleration was set to a={10}^{23}\left[\frac{m}{s^2}\right])

The three scenarios discussed above provide substantial experimental support that the new atom model can explain various physical properties of particles and elements, as well as anticipate the results of electrodynamic interactions in ways that prior models could never do.

The EMR absorption or emission can be determined by the total energy equation (5).

Analyzing the Values of the Terms of the Total Energy Equation

The total energy of a system of charges is determined by its electrodynamic interaction. This energy is calculated using a combination of motion variables such as relative distance, velocity, and acceleration. Many combinations of these three variables can result in the same energy magnitude. The example that follows displays only one of the possible combinations for each of the spectral lines used in the calculations.

As an example, let’s graph the spectral lines of the typical four lines of hydrogen emission as shown in Fig. 19. This is a contour or level graph of frequency with respect to distance and acceleration. The box below the graph displays the frequency values in Hz.

Emission spectrum of hydrogen from 9.11\ {10}^{12}Hz to 1.19\ {10}^{15}Hz, showing the four typical lines at approximately (460, 620, 691, and 7.32) {10}^{14}Hz (velocity was set to v={10}^6\left[\frac{m}{s}\right])

From Planck’s equation we get the frequency and energy of the four lines:

Line at 656 nm => f=4.57\ {10}^{14}\ [Hz] => E\approx3\ {10}^{-19}\ [J]

Line at 486 nm => f=6.17\ {10}^{14}\ [Hz] => E\approx4\ {10}^{-19}\ [J]

Line at 434 nm => f=6.91\ {10}^{14}\ [Hz] => E\approx4.5\ {10}^{-19}\ [J]

Line at 410 nm => f=7.31\ {10}^{14}\ [Hz] => E\approx4.8\ {10}^{-19}\ [J]

The four thick black lines on the graph correspond approximately to the frequencies above.

We’ll choose a specific distance on the graph, say r=6\ {10}^{-8}[m], to read the acceleration corresponding to the four black spectral lines in order to calculate the total energy and the value of each term that makes it, that is, the potential energy, the kinetic energy depending on velocity, and the kinetic energy depending on acceleration.

- Approximate frequency for line at 656 nm => f\approx4.60\ {10}^{14}\ [Hz], for a=1.98\ {10}^{23}[\frac{m}{s^2}]

The total energy: E=kq_1q_2\left(\frac{1}{r}-\frac{1}{r_i}\right)-\frac{kq_1q_2}{c^2}\left(\frac{1}{r}-\frac{1}{r_i}\right)\cdot v^2-\frac{2kq_1q_2}{c^2}\left(\ln{\left(r_i\right)}-\ln{\left(r\right)}\right)\cdot a=3.03\ {10}^{-19}[J]

The terms of the total energy equation:

U=kq_1q_2\left(\frac{1}{r}-\frac{1}{r_i}\right)=-1.53\ {10}^{-20}\ [J]

K=-\frac{kq_1q_2}{c^2}\left(\frac{1}{r}-\frac{1}{r_i}\right)v^2=-1.70\ {10}^{-25}\ [J]

E_{rad}=-\frac{2kq_1q_2}{c^2}\left(\ln{\left(r_i\right)}-\ln{\left(r\right)}\right)a=3.19\ {10}^{-19}\ [J]

- Approximate frequency for line at 486 nm => f\approx6.20\ {10}^{14}\left[Hz\right], for a=2.64\ {10}^{23}[\frac{m}{s^2}]

The total energy: E=kq_1q_2\left(\frac{1}{r}-\frac{1}{r_i}\right)-\frac{kq_1q_2}{c^2}\left(\frac{1}{r}-\frac{1}{r_i}\right)\cdot v^2-\frac{2kq_1q_2}{c^2}\left(\ln{\left(r_i\right)}-\ln{\left(r\right)}\right)\cdot a=4.10\ {10}^{-19}[J]

The terms U and K don’t change.

E_{rad}=-\frac{2kq_1q_2}{c^2}\left(\ln{\left(r_i\right)}-\ln{\left(r\right)}\right)a=4.25\ {10}^{-19}\ [J]- Approximate frequency for line at 434 nm => f\approx6.91\ {10}^{14}\ [Hz], for a=2.93\ {10}^{23}[\frac{m}{s^2}]

The total energy: E=kq_1q_2\left(\frac{1}{r}-\frac{1}{r_i}\right)-\frac{kq_1q_2}{c^2}\left(\frac{1}{r}-\frac{1}{r_i}\right)\cdot v^2-\frac{2kq_1q_2}{c^2}\left(\ln{\left(r_i\right)}-\ln{\left(r\right)}\right)\cdot a=4.57\ {10}^{-19}[J]

The terms U and K don’t change.

E_{rad}=-\frac{2kq_1q_2}{c^2}\left(\ln{\left(r_i\right)}-\ln{\left(r\right)}\right)a=4.72\ {10}^{-19}\ [J]- Approximate frequency for line at 410nm => f\approx7.32\ {10}^{14}\ [Hz], for a=3.10\ {10}^{23}[\frac{m}{s^2}]

The total energy: E=kq_1q_2\left(\frac{1}{r}-\frac{1}{r_i}\right)-\frac{kq_1q_2}{c^2}\left(\frac{1}{r}-\frac{1}{r_i}\right)\cdot v^2-\frac{2kq_1q_2}{c^2}\left(\ln{\left(r_i\right)}-\ln{\left(r\right)}\right)\cdot a=4.84\ {10}^{-19}[J]

The terms U and K don’t change.

E_{rad}=-\frac{2kq_1q_2}{c^2}\left(\ln{\left(r_i\right)}-\ln{\left(r\right)}\right)a=4.99\ {10}^{-19}\ [J]For this particular situation, and because we are working with electromagnetic radiation, it is clear that the radiation energy term provides the system’s overall energy.

Nuclear Energy Emission and Absorption

Nuclear energy is in the high-frequency band of the electromagnetic spectrum, and nuclear spectral lines can be detected using highly specialized semiconductor detectors.

It is obvious that the total energy equation (5) can also be used to calculate nuclear energy emission/absorption. The result is always determined by the electromagnetic interactions among charges.

In the paper “Negative Mass and Negative Refractive Index in Atom Nuclei – Nuclear Wave Equation – Gravitational and Inertial Control” [10], we computed nuclear frequencies (energy levels) using a different approach based on the Fast Fourier Transform. Although the computations are for the element aluminum, they demonstrate an alternative approach to determining energy emission or absorption.

Furthermore, in that work, a nuclear wave function was developed, which accounts for nuclear frequency (energy) emission or absorption in the aluminum element and suggests some emission lines may be nuclear in origin.

A more fundamental and general wave function is developed for the new atom model in the final phase of the present study, which will provide us with detailed energy information based on electromagnetic interactions across diverse environments.

The Electromagnetic Field of the New Atomic Model

As of yet, the only mathematical equations we have are some with fairly poor physical properties. As previously mentioned, the charge value of the atom (elementary toroidal charge fiber helix) is either +e/3 or -e/3, where e is the electron charge. With a surface charge density of \sigma=\frac{dq}{dS}, this charge is uniformly distributed on the fiber surface.

We’ll use the Universal Electrodynamic Force to determine the EMF for the modern atomic model discussed in this paper. The electromagnetic field generated by the relative motion of two charges is defined by this force. The research Nuclear Fusion Enhanced by Negative Mass – A Proposed Method and Device – (Part 1) provides a brief explanation of the Universal Force terms.

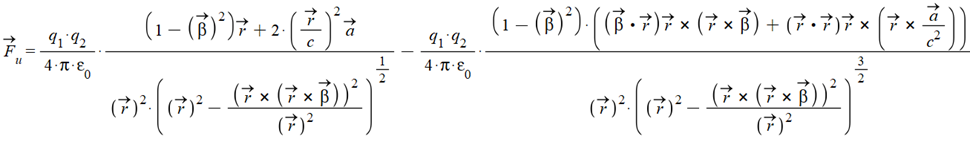

The Universal Electrodynamic Force [10] in vectorial form is:

Where \vec{\beta}=\frac{\vec{v}}{c}, and \vec{r},\ \vec{v},\ \vec{a}, are the relative position, velocity, and acceleration between the two charges.

In general, velocity and acceleration may not point in the same direction. Let’s define their angles with respect to the vector \vec{r}.

\theta: angle between \vec{r} and \vec{v}

\alpha: angle between \vec{r} and \vec{a}

The motion variables we are going to use in the Universal Force are those given in Eqs. (2) by vector \vec{r} and its derivatives.

The Universal Force with velocity and acceleration projected in the direction of \hat{r} is:

{\vec{F}}_u=\frac{kq_1q_2}{r^2}\ \left(\frac{\left(\left(1-\beta^2\right)\ r+\frac{2\ r}{c^2}\left(\vec{a}\cdot\vec{r}\right)\right)}{r\ \left(1-\beta^2\sin^2{\left(\omega_ht\right)}\right)^\frac{1}{2}}-\frac{\left(1-\beta^2\right)\left(\left(\beta^2r^2\cos^2{\left(\omega_ht\right)}+\frac{r^2\left(\vec{a}\cdot\vec{r}\right)}{c^2}\right)r-\beta\ r^3\cos{\left(\omega_ht\right)}\cdot\frac{v\ \cos{\left(\omega_ht\right)}}{c}-\frac{r^3}{c^2}\left(\vec{a}\cdot\vec{r}\right)\right)}{r^3\ \left(1-\beta^2\sin^2{\left(\omega_ht\right)}\right)^\frac{3}{2}}\right)\ \hat{r}Where: r ={\|\mathit{{\vec{r}}}\|}; v ={\|\mathit{{\dot{{\vec{r}}}}}\|}; \beta =\frac{{\|{\dot{{\vec{r}}}}\|}}{c}; k\ = Coulomb constant.

We may calculate the EMF by making q_2 the test charge. The charge q_1 will be replaced by an element of the helix surface charge dq_h. The differential field caused by this element of helix charge is:

\frac{d{\vec{F}}_u}{q_2}={d\vec{\varphi}}_h\left(r,t\right)=\frac{k\ dq_h}{r^2}\left(\frac{\left(\left(1-\beta^2\right)r+\frac{2r}{c^2}\left(\vec{a}\cdot\vec{r}\right)\right)}{r\left(1-\beta^2\sin^2{\left(\omega_ht\right)}\right)^\frac{1}{2}}-\frac{\left(1-\beta^2\right)\left(\left(\beta^2r^2\cos^2{\left(\omega_ht\right)}+\frac{r^2\left(\vec{a}\cdot\vec{r}\right)}{c^2}\right)r-\beta r^3\cos{\left(\omega_ht\right)}\cdot\frac{v\cdot\cos{\left(\omega_ht\right)}}{c}-\frac{r^3}{c^2}\left(\vec{a}\cdot\vec{r}\right)\right)}{r^3\left(1-\beta^2\sin^2{\left(\omega_ht\right)}\right)^\frac{3}{2}}\right)\hat{r}This field equation can be expressed concisely as follows:

{d\vec{\varphi}}_h\left(r,t\right)=\phi_h\ {dq}_h\ \hat{r} (12)

With:

\phi_h=\frac{k}{r^2}\left(\frac{\left(\left(1-\beta^2\right)r+\frac{2r}{c^2}\left(\vec{a}\cdot\vec{r}\right)\right)}{r\left(1-\beta^2\sin^2{\left(\omega_ht\right)}\right)^\frac{1}{2}}-\frac{\left(1-\beta^2\right)\left(\left(\beta^2r^2\cos^2{\left(\omega_ht\right)}+\frac{r^2\left(\vec{a}\cdot\vec{r}\right)}{c^2}\right)r-\beta r^3\cos{\left(\omega_ht\right)}\cdot\frac{v\cdot\cos{\left(\omega_ht\right)}}{c}-\frac{r^3}{c^2}\left(\vec{a}\cdot\vec{r}\right)\right)}{r^3\left(1-\beta^2\sin^2{\left(\omega_ht\right)}\right)^\frac{3}{2}}\right) (13)

The surface charge density of the helix is \sigma=\frac{dq}{dS}, dq=\sigma dS=\sigma2\pi r_f|d\vec{l}|, where |d\vec{l}| is the differential length of the helix, which is the same as |d\vec{r}|, then dq=\sigma2\pi r_f|d\vec{r}|. However, we can write {\|d {\vec{r}}\|}={\|{\dot{{\vec{r}}}}\|}\mathit{dt} so that:

\mathit{dq} =\sigma 2\pi r_{f}{\|{\dot{{\vec{r}}}}\|}\mathit{dt} (14)

The total surface charge density is given by the total helix charge divided by the helix surface, \sigma=\frac{Q}{S_h}, where the helix surface is S_h=2\pi r_fL=2\pi r_f2\pi R=4\pi^2r_fR, so \sigma=\frac{Q}{4\pi^2r_fR} (15). Note that due to the small helix radius, the total helix length is L\approx2\pi\ R. Replacing (15) and (14) in (12), the differential field becomes:

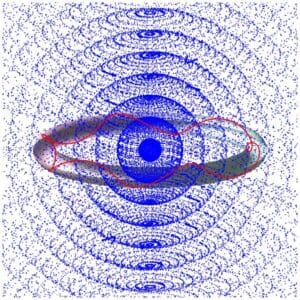

Electromagnetic field of the new atomic model (not in scale)

d{\vec{\varphi}}_h\left(r,t\right)=\phi_h\frac{Q}{2\pi R}|\dot{\vec{r}}|dt\ \hat{r} (16)

The integration along the total number of helix periods required to complete a torus turn, which is equal to the time for one torus period, or T=\frac{2\pi}{\omega_R}, yields the total EMF:

{\vec{\varphi}}_h\left(r,t\right)=\int_{0}^{\frac{2\pi}{\omega_R}}\phi_h\cdot\frac{Q}{2\pi R}\cdot|\dot{\vec{r}}|dt\ \hat{r}Since E_h\left(r,t\right){=\phi}_hQ represents the helix’s EMF, the final total electromagnetic field equation for the new atomic model is as follows:

{\vec{\varphi}}_h\left(r,t\right)=\frac{1}{L}\ \int_{0}^{\frac{2\pi}{\omega_R}}{E_h\left(r,t\right)\left|\dot{\vec{r}}\right|dt}\ \hat{r}\left(t\right) (17)

A graph of the electromagnetic field of the new atom (not in scale) is shown in Fig. 20.

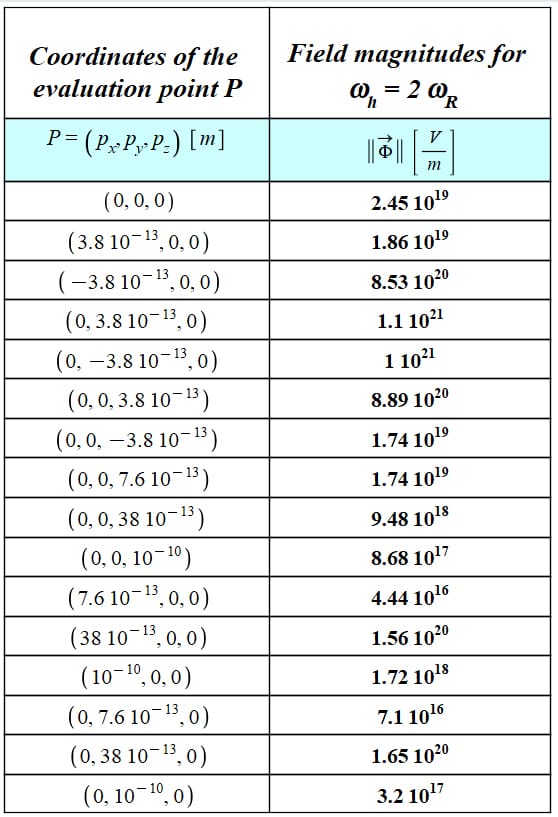

Magnitude of the Electromagnetic Field of the New Atomic Model

The magnitude of the new atom’s electromagnetic field was evaluated at various distances

The magnitude of the field calculated by Eq. (17) requires a certain amount of computing power. To make the work easier on the computer, the integral was numerically calculated with a “medium” resolution, which provides a rough approximation of the EMF magnitude.

Figure 21 depicts the calculation of field magnitudes at several locations. The origin of coordinates is both the central point of the torus circumference (x-y plane) and the evaluation point P.

The field magnitude has been calculated at diverse locations in the x, y, and z directions, with z being the axis perpendicular to the torus. As mentioned before, the values are rough approximations and subject to distance and symmetrical mismatches.

If we look at the two rows before the last one, it is clear that the field cannot be stronger at longer distances.

The integration approximation also yields to a lack of symmetry in field magnitudes on one axis and for opposite directions, as can be seen in the table of Fig. 21.

Nonetheless, and despite the limited computer capabilities available, we may have some notion of the vast magnitude of the electromagnetic field generated by the new atom model.

Derivation of the Real-Valued Wave Function of the New Atom Model

We have previously derived the new atom’s electromagnetic field, which is described in Eq. 17. We can build a more general EMF equation that is valid for any time t.

{\vec{\varphi}}_h(r,t)=\frac{1}{L}\ \int_{0}^{t}{E_h\left(r,t\right)}|\dot{\vec{r}}|dt\ \hat{r}(t) (18)

Two wave functions will be derived from the EMF equation (18):

- A homogeneous wave function (no external field applied to the atom)

- A wave function by considering the action of an external EMF acting on the atom

Homogeneous Wave Function of the New Atomic Model (no external EMF applied to the atom)

The total derivative of Eq. (18) is:

d{\vec{\phi}}_h\ =\frac{1}{L}\left(\left(\int_{0}^{t}{\left(\frac{\partial}{\partial r}E_h\left(r,t\right)\right)\dot{\vec{r}}\left(t\right)dt}-\frac{\partial}{\partial r}E_e\left(r,t\right)\right)\hat{r}\left(t\right)dr+\left(\left(E_h\left(r,t\right)\dot{\vec{r}}\left(t\right)-\frac{\partial}{\partial t}E_e\left(r,t\right)\right)\hat{r}\left(t\right)+\left(\int_{0}^{t}{E_h\left(r,t\right)\dot{\vec{r}}\left(t\right)dt}-E_e\left(r,t\right)\right)\left(\dot{\theta}\left(t\right)\hat{\theta}\left(t\right)+\dot{\phi}\left(t\right)\sin{\left(\theta\left(t\right)\right)}\hat{\phi}\left(t\right)\right)\right)dt\right) (19)

To simplify the derivation method and avoid writing long equations, the resulting derivative functions will be specified merely as A(\vec{r},t) and B(\vec{r},t).

The derivative of (19) with respect to r will give a certain function A(\vec{r},t), that is: \frac{\partial}{\partial r}\left({\vec{\Phi}}_h\right)=A(\vec{r},t).

Now we take the time derivative of A(\vec{r},t): \frac{\partial}{\partial t}\left(A(\vec{r},t)\right)=\frac{\partial^2}{\partial r\partial t}\left({\vec{\Phi}}_h\right) (20)

The time derivative of (19) will give a certain function B(\vec{r},t), that is: \frac{\partial}{\partial t}\left({\vec{\Phi}}_h\right)=B(\vec{r},t).

Now we take the derivative of B(\vec{r},t) with respect to r: \frac{\partial}{\partial r}\left(B(\vec{r},t)\right)=\frac{\partial^2}{\partial t\partial r}\left({\vec{\Phi}}_h\right) (21)

Since we are working with a finite-size particle, our base equation will not exhibit any discontinuity. Therefore, we can equate Eq. (20) with Eq. (21), which gives us:

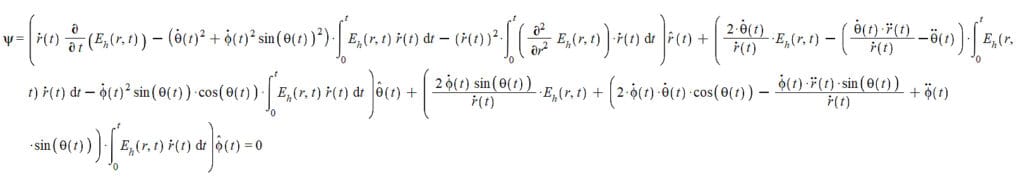

(22)

It’s important to distinguish between the polar angle \theta(t) and the angle \theta between the vectors \vec{r} and \vec{v}. The toroidal helix’s central axis is on the xy plane, and because the helix has an extremely small radius, we have \theta(t)\approx\frac{\pi}{2}. In contrast, the azimuthal angle \phi(t)=\omega_Rt has two derivatives: \dot{\phi}\left(t\right)=\omega_R and \ddot{\phi}\left(t\right)=0. Then, our equation (22) reduces to:

(23)

Applying the divergence to Eq. (23) gives us the homogeneous integro-differential wave function of the new atom:

\Psi(r,t)=\frac{\partial}{\partial t}\left(E_h\left(r,t\right)\right)-\frac{\dot{r}\left(t\right)}{2\ r\left(t\right)}\int_{0}^{t}\left(\left(\frac{\partial^3}{\partial r^3}E_h\left(r,t\right)\right)\dot{r}\left(t\right)\right)dt-\dot{r}\left(t\right)\int_{0}^{t}\left(\left(\frac{\partial^2}{\partial r^2}E_h\left(r,t\right)\right)\dot{r}\left(t\right)\right)dt-\frac{r\left(t\right)\ \omega_R^2}{2\ \dot{r}\left(t\right)}\int_{0}^{t}\left(\left(\frac{\partial}{\partial r}E_h\left(r,t\right)\right)\dot{r}\left(t\right)\right)dt+\frac{r\left(t\right)}{2}\left(\frac{\partial^2}{\partial r\partial t}E_h\left(r,t\right)\right)-\frac{\omega_R^2}{\dot{r}\left(t\right)}\int_{0}^{t}\left(E_h\left(r,t\right)\ \dot{r}\left(t\right)\right)dt=0 (24)

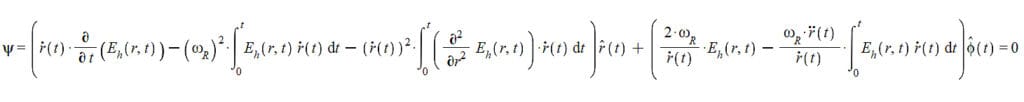

Non-homogeneous Wave Function of the New Atomic Model (external EMF applied to the atom)

For this derivation, we’ll assume that the atom is affected by an external electromagnetic field {\vec{E}}_e\left(r,t\right). The interaction between the atomic self EMF and the external EMF is given by applying Newton’s second law, which after some little algebra results in:

\vec{\varphi}\left(r,t\right)=\frac{1}{L}\ \int_{0}^{t}{E_h\left(r,t\right)\left|\dot{\vec{r}}\right|dt}\ \hat{r}\left(t\right)\ ={\vec{E}}_e(r,t) (25)

Following the same derivation technique as for the homogeneous wave function, we arrive at the final integro-differential wave function of the new atom when subjected to external electromagnetic fields:

-\frac{\dot{\vec{r}}\left(t\right)}{2}\int_{0}^{t}{\left(\frac{\partial^3}{\partial r^3}E_h\left(r,t\right)\right)\dot{\vec{r}}\left(t\right)d}t-\dot{\vec{r}}\left(t\right)\int_{0}^{t}{\left(\frac{\partial^2}{\partial r^2}E_h\left(r,t\right)\right)\dot{\vec{r}}\left(t\right)d}t-\frac{\omega_R^2}{2\dot{\vec{r}}\left(t\right)}\int_{0}^{t}{\left(\frac{\partial}{\partial r}E_h\left(r,t\right)\right)\dot{\vec{r}}\left(t\right)d}t+\frac{1}{2}\ \frac{\partial^2}{\partial r\partial t}E_h\left(r,t\right)-\frac{\omega_R^2}{\dot{\vec{r}}\left(t\right)}\int_{0}^{t}{E_h\left(r,t\right)\ \dot{\vec{r}}\left(t\right)d}t+\frac{\partial}{\partial t}E_h\left(r,t\right)=-\frac{\dot{\vec{r}}\left(t\right)}{2}\ \frac{\partial^3}{\partial r^3}E_e\left(r,t\right)-\dot{\vec{r}}\left(t\right)\frac{\partial^2}{\partial r^2}E_e\left(r,t\right)-\frac{\omega_R^2}{2\dot{\vec{r}}\left(t\right)}\ \frac{\partial}{\partial r}E_e\left(r,t\right)-\frac{1}{2\dot{\vec{r}}\left(t\right)}\ \frac{\partial^3}{\partial r\partial t^2}E_e\left(r,t\right)-\frac{\ddot{\vec{r}}\left(t\right)}{2\dot{\vec{r}}\left(t\right)^2}\ \frac{\partial^2}{\partial r\partial t}E_e\left(r,t\right)+\frac{1}{\dot{\vec{r}}\left(t\right)}\ \frac{\partial^2}{\partial t^2}E_e\left(r,t\right)-\frac{\ddot{\vec{r}}\left(t\right)}{\dot{\vec{r}}\left(t\right)^2}\ \frac{\partial}{\partial t}E_e\left(r,t\right)-\frac{\omega_R^2}{\dot{\vec{r}}\left(t\right)}E_e\left(r,t\right) (26)

The behavior of Mother Nature, or the real world, is based on real-valued measurements rather than complex numbers. Imaginary numbers do not represent the real physical universe.

The new atom model developed in this study, with a finite size, elastic properties, and a self-electromagnetic field that extends to infinity, cannot have an imaginary wave function like Schrödinger’s, but must instead have a real-valued wave function.

The new atomic model’s wave functions, given by Eq. (24) and Eq. (26), contain the Volterra integral, serving as a fundamental demonstration of “causality” for a novel atomic model in the real physical world.

Eq. (24) defines the new atomic model’s real-valued wave function.

The solution to the atomic integro-differential equations will be pending until I have time to devote to them, which is not possible at the time of writing.

You are welcome to try to find the solution to both wave functions. If you get it before I do, I kindly ask you to share your results in order to be published here with the due credits. As an additional recognition for your effort, you will be a member of the Guests of Honor section of the website.

As a closure of the present study, we can say that the mathematical model that fully describes the new atomic theory is thus given by four equations: vector \vec{r} from Eqs. (2), Eq. (17), Eq. (24), and Eq. (26).

Conclusions

The new atomic model is based on the electron morphology theory that originated from the extensive experimental results from Compton, which was later extended and improved by Bostick, one of his students and a great experimentalist.

It has been demonstrated that experimental results validate the new atomic model proposed in this paper.

The atom model developed in the current study has dimensions and finite energy; it is not a “point particle” with infinite energy.

This modern atomic model explains all subatomic particles discovered up to now and can predict new particles still to be discovered.

It was demonstrated that the more than proven laws of electrodynamics fully accounted for the development of the new atom model.

No obscure concepts based on randomness or the rejection of causality, as in quantum theory, can be applied to make a real physical atom model.

It has been demonstrated that, up to now, there is no better atom model capable of providing true physical explanations for the numerous physical properties of particles and elements than this new one.

Clear proof was given about the physical origin of discrete energies from a finite-size, real-world atom. There are no mysterious magic energy jumps as described in quantum theory.

It was demonstrated that the new atomic model clearly explains not only the cause of discrete or “quantized” energies but also the origins of Planck’s and Rydberg’s constants.

Proof was given that the total energy equation predicts experimentally found spectral lines for elements (wrongly named “atoms”), as well as new lines that have yet to be discovered.

The derivation of the atomic real-valued wave function demonstrates that a finite-size particle cannot have an imaginary wave function like that developed by Schrödinger, which does not describe a real physical world.

Bibliography

[1]. Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, https://www.fnal.gov/pub/science/inquiring/matter/madeof/

[2]. Arthur H. Compton, “The size and shape of the electron” (1918), Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences, Vol. 8, No. 1, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24521544

[3]. Winston H. Bostick, “The Morphology of the Electron”, International Journal of Fusion Energy, Vol. 3 No. 1, pp. 10-53 (1985), http://wlym.com/archive/fusion/ijfe/19850101-IJFE.pdf

[4]. David L. Bergman, J. Paul Wesley, “Spinning Charged Ring Model of Electron Yielding Anomalous Magnetic Moment” (1990).

[5]. David L. Bergman, “Modeling the Real Structure of an Electron” (2010), Foundations of Science.

[6]. Joseph Lucas and Charles W. Lucas, Jr., “A Physical Model for Atoms and Nuclei”, Galilean Electrodynamics, Volume 7, Number 1 (1996), Foundations of Science (2002-2003), Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4.

[7]. David L. Bergman, “Shape & Size of Electron, Proton & Neutron” (2004), Foundations of Science.

[8]. Raul Fattore, “What is Charge? – The Redefinition of Atom – Energy to Matter Conversion” (2023), https://physics-answers.com/what-is-charge-the-redefinition-of-atom-energy-to-matter-conversion/

[9]. Charles W. Lucas, Jr., “A Classical Electromagnetic Theory of Elementary Particles” (2004-2005), Part 1, Part 2

[10]. Raul Fattore, “Negative Mass and Negative Refractive Index in Atom Nuclei – Nuclear Wave Equation – Gravitational and Inertial Control” (2023), Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6

[11]. Raul Fattore, “Nuclear Fusion Enhanced by Negative Mass – A Proposed Method and Device” (2024), Part 2

[12]. Raul Fattore, “Nuclear Fusion Enhanced by Negative Mass – A Proposed Method and Device” (2024), Part 3

[13]. Raul Fattore, “Negative Mass and Negative Refractive Index in Atom Nuclei – Nuclear Wave Equation – Gravitational and Inertial Control” (2023), Part 1

[14]. Labov, S. E. & Bowyer, S., “Spectral observations of the extreme ultraviolet background” (1991), Astrophysical Journal, Part 1, vol. 371, p. 810-819

[15]. Jean-Yves Roncin and Françoise Launay, “Atlas of the Vacuum Ultraviolet Emission Spectrum of Molecular Hydrogen”, Monograph No. 4, (1994), Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, National Institute of Standards and Technology

Related articles:

What is Charge? – The Redefinition of Atom – Energy to Matter Conversion

Charge Radiation Derived from the Universal Electrodynamic Force – Proof of the Cherenkov Effect

Nuclear Fusion Enhanced by Negative Mass – A Proposed Method and Device